How I read nonfiction books

you gotta write to read

Nonfiction books can change your life for the better. My life took a different path after I read Getting Things Done by David Allen. Since then, I started reading more and more nonfiction books - I try to do one fiction, one nonfiction book (though I admit I read the entire Cosmere universe books by Brandon Sanderson without stopping for air).

While I love reading nonfiction books, over time I realized I have very little retention of most books I’ve read in the past. While I wouldn’t say it was a waste of time1, I wanted to have better recall of what I read.

In this post, I’ll describe my solution to the retention problem - a process for creating literature notes for nonfiction books. I find that when I do this, I don’t only increase retention. I get much more out of the book than just remembering what it says. I interact with the subject matter. I think about it deeply. I connect it to other ideas. I think, and I learn. I get these benefits even if the book is mediocre - thinking about the subject matter elevates it. Nonfiction becomes a thinking tool, a jumping-off point to improving my mental models of how I see the world.

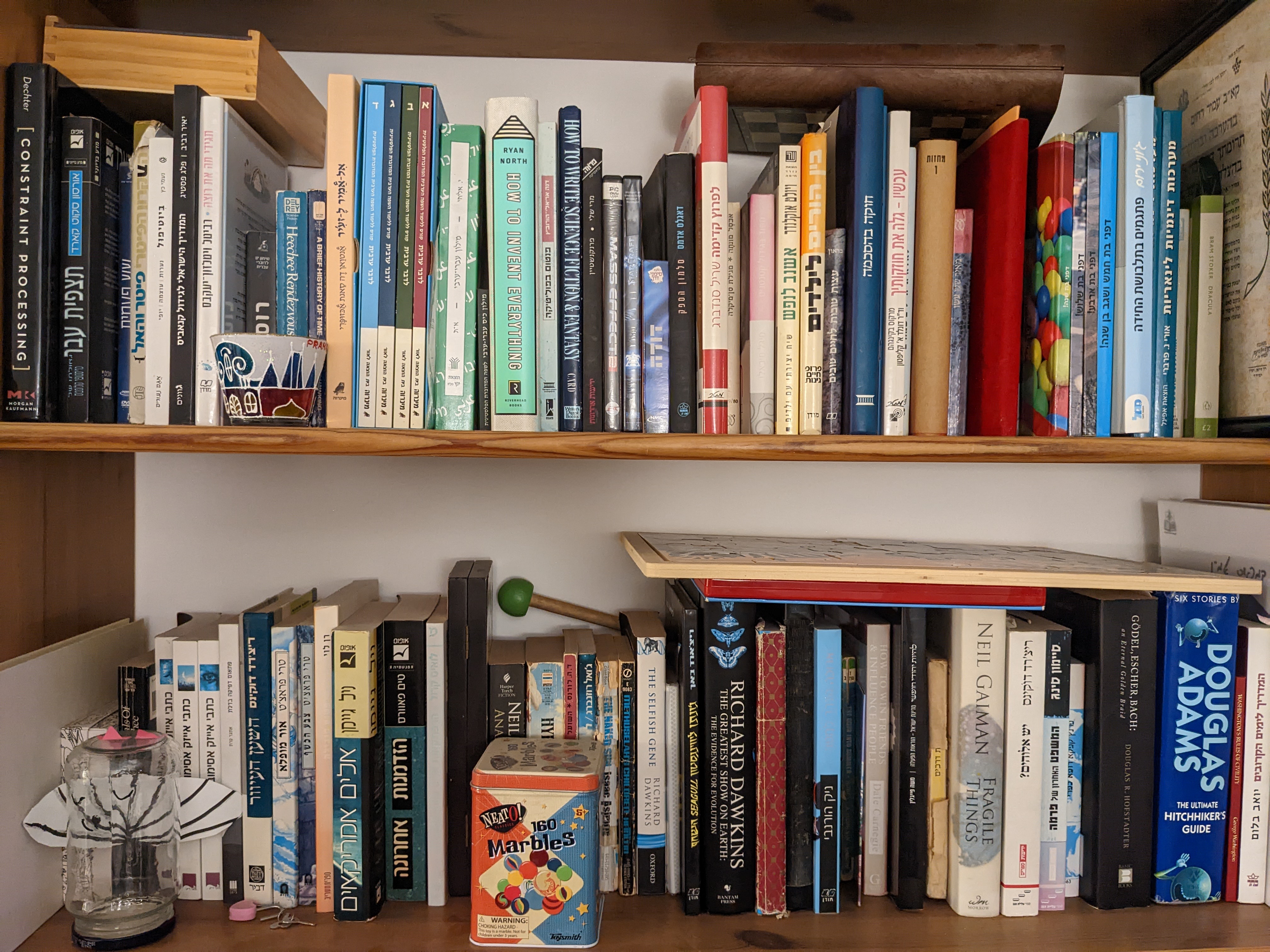

gotta have some room for the kids' junk, too!

gotta have some room for the kids' junk, too! At this point you might be thinking “ain’t nobody got time for this shit”, but here’s my pitch: you can spend 10 hours reading a book and vaguely remember maybe one or two different points it makes. If you go through the trouble of using this method, you could spend twice as much time on the same book, BUT you’ll remember more than twice the content. Minute for minute, this is a better deal. Those minutes would be harder, but it’s worth it. Even more, every book you digest like this has a compounding effect - you’ll have more connection to make from previous books, more insights, you’ll be able to contrast one book with another and find the truth amidst multiple points of view. The more you do this, the more it pays off.

That said, I don’t do the whole shebang for each and every nonfiction book I read. More on this below.

Literature notes

Literature notes (or litnotes as the cool kids say2) vary from person to person, but here’s how I see them: literature notes describe a source of information, such as a book, article, blog post, YouTube video, conference lecture, etc. Literature notes describe what the source is saying and don’t attempt to be objectively true. It is useful to have an accurate description of the source regardless of whether or not I buy in to the idea itself. When I research a topic, I might read a lot of resources about that topic and I may agree or disagree with what those resources are saying, but it makes sense to pull out important information to synthesize my own thinking on the topic in the form of a permanent note later on.

You can keep literature notes however you like - analog, digital, anything goes. As for me, about two years ago I started using Obsidian, a note-making tool. It’s my second brain - I use it for everything from a shopping list to working on my social anxiety, from writing down a comedy skit draft for TikTok (I don’t do comedy or TikTok, but hey!) to documenting how to create 3D models using code. All of my literature notes go in Obsidian.

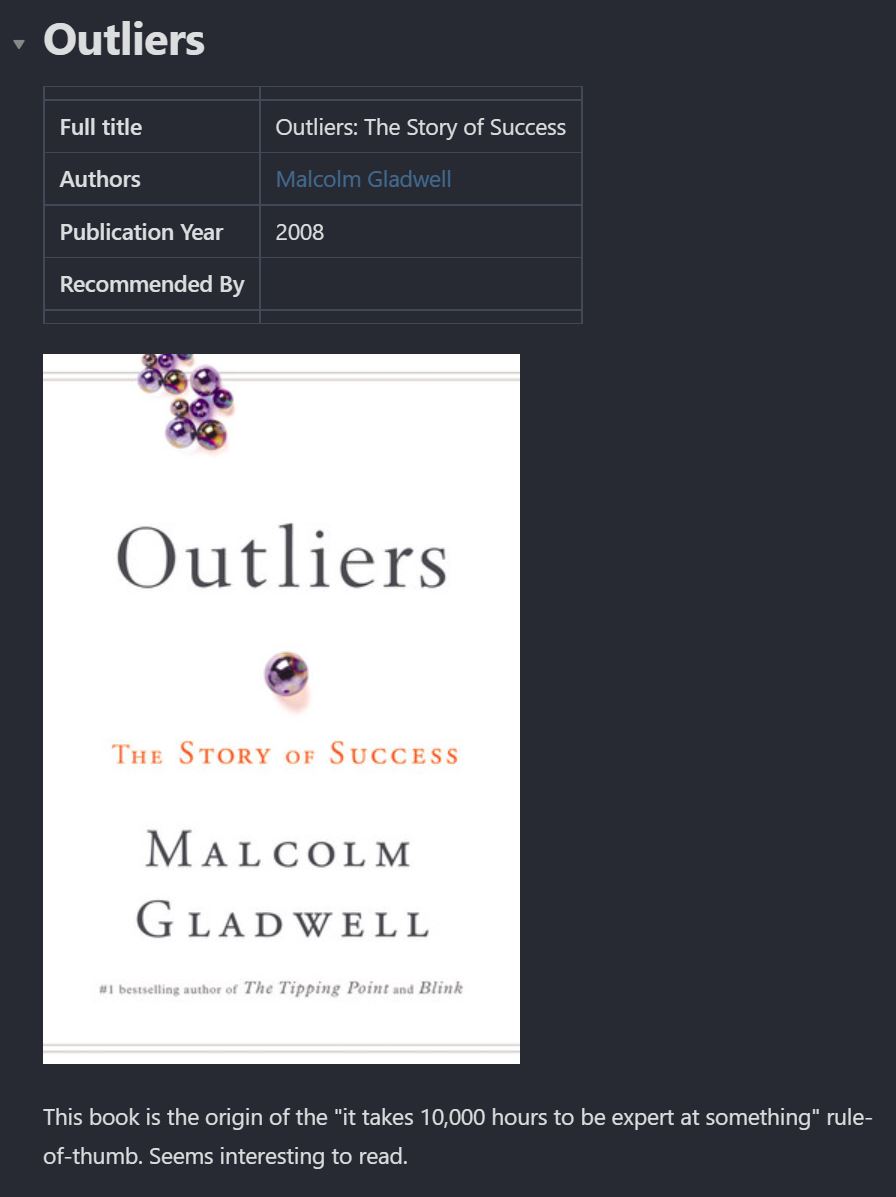

Note to self: read this!

First, when I get a book recommendation, I head over to its Goodreads page and create a book note template (under a “Literature Notes” directory) using Booksidian3. This creates a note that looks like “Thinking in Bets (book)”. My book note template has some basic fields and also a “Recommended by” slot which I make sure to fill out. People in my life each have their own note, so I use the linked name of the person who recommended me the book. If there’s a specific context, like “Mark recommended this because I told him I liked the movie Memento”, I add that too. It’s kinda nice to see that from that person’s note in the backlinks. In addition, if applicable, I try to write out if there’s a specific reason I’m inclined to read the book - am I looking to get something specific out of it?

At this point, it looks like this:

I then add the book as a direct link from a “Reading List” note. That’s it for now, until I actually start reading the book.

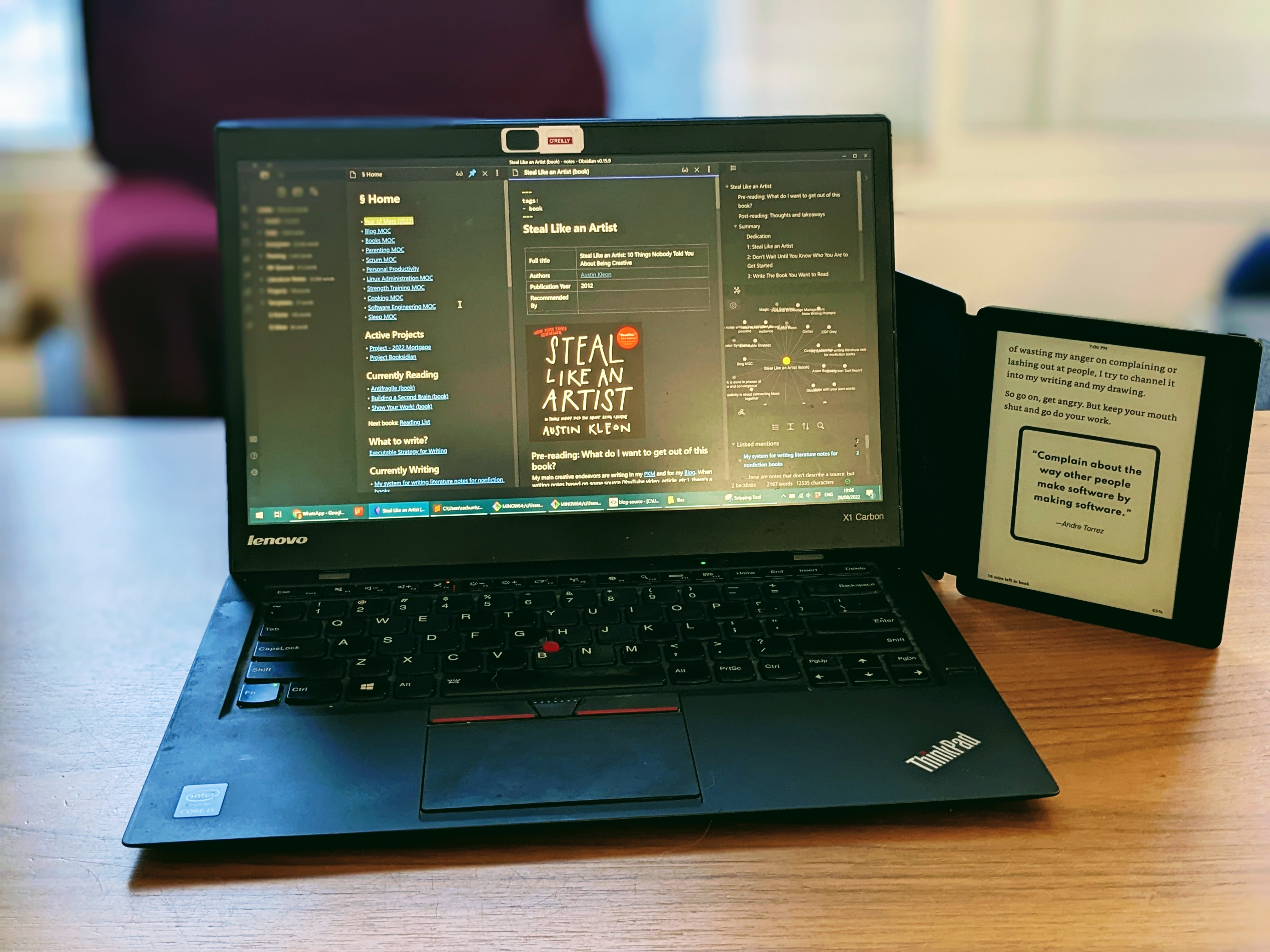

Gotta actually read! Like… like school!

As I start reading the book, I add a link to it from my “Home” note under “Reading now”. Now, my system involves reading the e-book and the audiobook intermittently. I use a physical Kindle with audiobooks from Audible. The killer feature of this combination is that they offer Whispersync™ - the e-book and the audiobook can sync up to where you are in the book. This means I can listen to it in the car on the way home and continue from where I left off when I open my Kindle before going to sleep. It changed how, and mostly how much, I read.

While reading on the Kindle, I occasionally highlight some passages of interesting or for-whatever-reason noteworthy, but the majority of my highlighting happens later. There’s a bookmark feature in the Audible app for keeping sound clips, but I wish there was a way that it’ll automatically be converted to a Kindle highlight so it’ll show up on my Kindle notes. Alas, I just don’t use this feature.

After finishing the book, I move the book note link from “Reading List” to my “Books” notes, which contains links to books I’ve actually read. I do this for fiction books, too, by the way - everything so far I do for both. But the next part is for nonfiction only.

Easy part’s over

Next, after either finishing the book completely - or, with a long book, after reading a substantial part of it - I do a cycle of highlights, summary and synthesis on each chapter. Let’s grab a cup of coffee and get to work.

Step 1: Highlights

First, I go back and make highlights in the e-book version. I do this on my tablet or laptop with the Kindle app. Since I just finished the book (or the specific chapter), I have some feeling for what topics would have some interesting ideas to capture, so I’m quickly skimming the book for some gold nuggets.

There are a few reasons for doing this:

- Most of my “reading” is done with the audiobook while doing something else (e.g., driving), so I can’t highlight as I’m listening.

- Doing a second pass for highlighting also serves as a refresher on the book. I get another chance to catch something I missed, and I can do that after understanding the big-picture ideas of the book.

- It lets me enjoy the book more on the first read, not having to stop every few minutes to highlight and note something to myself (unless I have a particularly good insight that I just don’t want to miss, in which case I’ll even pause an audiobook to write something down)

After skimming through and highlighting, I use the Kindle “Note and Highlights” page to copy and paste all the highlight to the book’s literature note, under the correct chapter.

Step 2: Summary

Now, I go over the highlights and try to extract a short summary of the point that it’s making. I keep some of the highlights in place, as sometimes having specific quotes is valuable for the tone of the book, or where the highlight is already to-the-point. But I try to rephrase most of them and write with my own words.

The extent to which I do this changes a lot depending on the book. The more the book is aligned with my current interests at the moment, the more detailed the write-up. If the book is meh, I might just leave the highlights in the note and leave it at that. This isn’t school - there’s no extra credit for doing pointless busywork.

I might even choose different resolutions for different chapters. Some chapters might get hundreds of words while others I just skip.

Step 3: Synthesis

Up until now, I tried to be somewhat objective and describe what the book is claiming (and I’ll use language like “{author} claims that…” when a point made in the book is iffy) - now, I want to focus on what I think.

Easy recall requires multiple contexts and connections, so I try to attack a point that I want to remember from multiple angles. I do this mostly intuitively, but I also have a more analytical method that I use if I get stuck. It’s also very useful if you’re just starting out and don’t really know how to proceed.

The method is really simple - I have a bunch of prompts that I try to answer for any given point. I don’t force it - if one prompt doesn’t look promising, I move on to the next one.

Here’s my current collection of prompts:

Do I already have a note on this topic? I search my notes for something similar. If I do, I re-read the existing note. Does this new source add something valuable to the argument?

Do I agree with this point? Why (or why not)? What personal experience has led me to think that? Is this just a gut feeling or do I have proof?

What does this remind me of? I try to think about distinct and seemingly unrelated areas of interest. Does this relate to computer science? Personal productivity? Bodybuilding? Cooking? You’ll be surprised how common it is to find unexpected connections if you try hard enough. And if you do this enough, it gets easier and easier.

Can I make this point actionable for me in the near future? I think about current projects (work and personal). Can any of them be a testing ground for experimentation based on what I read?

Why is this not only true, but important?

Is this a special case of a stronger claim? Can this “prove” something more abstract?

Did I hear this claim from another source already? It can take a few times of hearing an argument before I decide to write a note for it. I try to think back if I’ve heard it before and write down some hints for more sources.

Does this apply to something I did in the past? Did I, or do I, unconsciously do it already and just never thought about it analytically?

Who in my life might agree or disagree with this?

Let’s take the first prompt, “Do I agree with this?”, and expand on it a little.

If I agree with the point and I feel like I want to dive deeper into it in the future, I’ll try to extract out an evergreen, atomic note from it. In short, these are notes that don’t describe a source, but rather make a very specific claim. For example, in Steal Like an Artist, author Austin Kleon says in the dedication:

It’s one of my theories that when people give you advice, they’re really just talking to themselves in the past. This book is me talking to a previous version of myself.

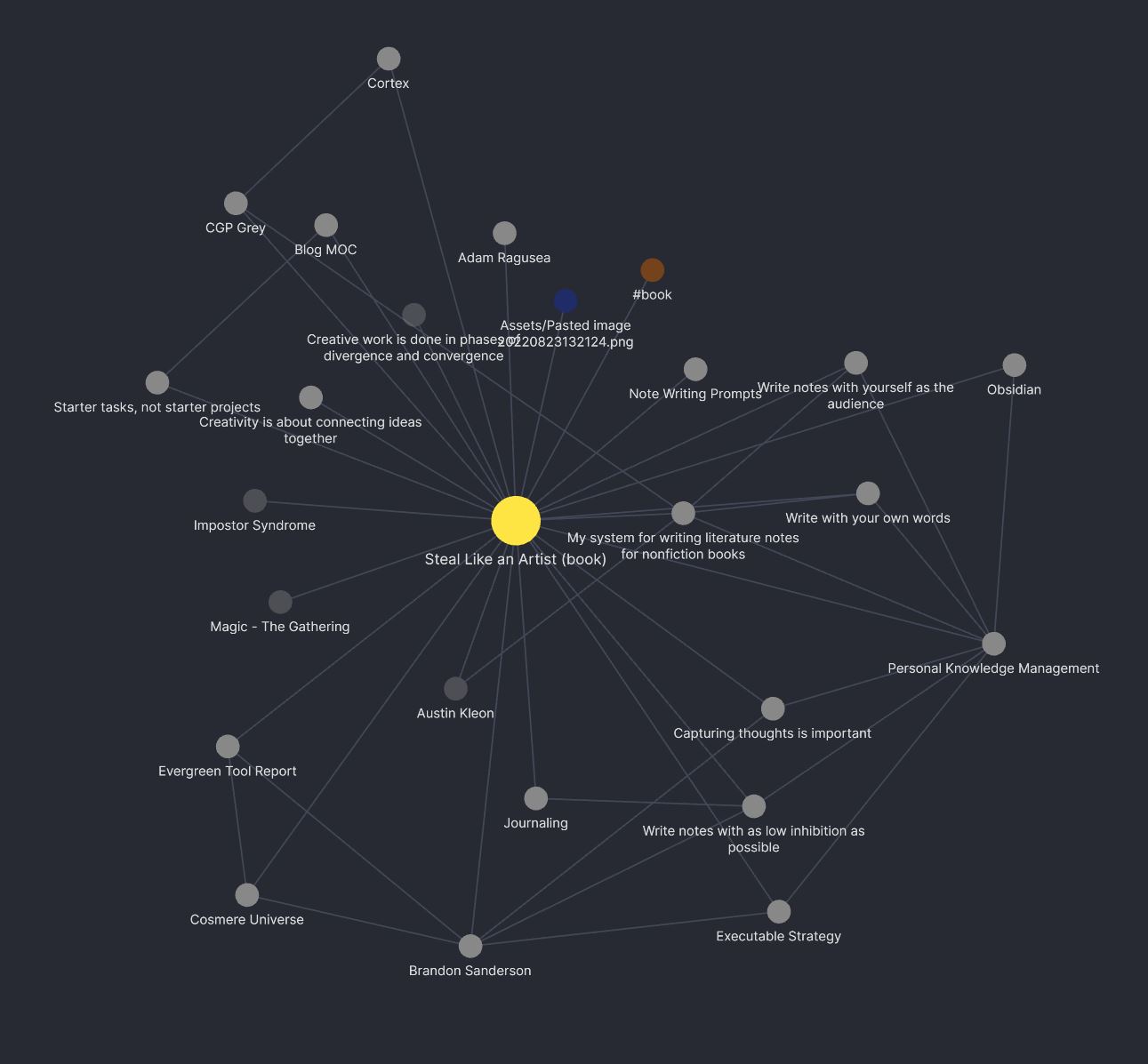

While reading this, I recalled that CGP Grey said that he also does this for his videos - thinks of past-him as the audience. Since I write a lot of notes, the audience question comes up a lot (in how to phrase things, how much to explain, etc.) and I find that targeting me-without-this-knowledge is a good way to be productive. When I read that line in the book, all of this came together and I created a note titled “Write with your past self as the audience”. And actually, once I did that I realized I already had a note “Write notes for future you”, so I merged and refactored both to “Write notes with yourself as the audience”, where I go over how to write both for your past-self (e.g., to explain something in a way that you’d understand if you haven’t had that specific knowledge) and for your future-self (e.g., to capture enough context so that it’ll be understandable in the future).

Now, sometimes I disagree with something. That’s just as good. If that’s the case, I try to think and explain why I disagree. This sometimes leads to the exact result - I’ll write a new atomic note with the opposite claim. It means that it doesn’t really matter if I agree with a source or not. The only important thing is thinking about a topic, and writing is thinking.

Sometimes, I already have some atomic evergreen notes on a subject. This is common, because I usually read books that align with my interests, so it’s safe to assume I’ve already read some other books on the same topic. In that case, I just link from the literature note to the evergreen note and sometimes I edit the evergreen note with new ideas. Sometime, it’s enough to add a link - I can also see backlinks (links to the current note) when I read the atomic note, so the next time I read it, it will point back to this new book as a source for the claim.

Example note

Let’s bring the abstract method down to concrete example. I think the only way to do this is sharing a real-life literature note I worked on recently. Below I’m attaching my note for Steal Like an Artist. Most “blue-link” text in the note is an Obsidian link. This means that either there’s a note with that title, or I’m planning to write one later.

Click here to see my note on Steal Like an Artist

If you also write literature notes, I’d love to hear how your process looks like!

Your brain is literally a neural network. Your attitude towards the world can change imperceptibly, ever-so-slightly changing weights when accepting new training data, even if the original input is gone. ↩︎

I doubt any cool kids say that, but I own this domain, so what are you gonna do about it? ↩︎

Full disclosure: I created Booksidian :) ↩︎

Follow me on Twitter and Facebook

Thanks to Yonatan Nakar, Ori Bar El, Ram Rachum, Daniel Yosef, Yosef Twaik, Yaniv Libal, Inbal Parvari, Hannan Aharonov and Haim Daniel for reading drafts of this.